Five million people come to the Grand Canyon every year and a handful don’t make it back alive. This is the story of one of those deaths, and what it can teach us.

Grand Canyon visitors get into trouble in all kinds of ways. They don’t carry enough water or food, they underestimate how strenuous the hike is, they don’t bring protection from the sun, they go off the trails, they fail to read maps or bring the right equipment. More than a thousand people require emergency help of some kind each year.

There are warnings everywhere, in multiple languages, in park guides, on signs and trail maps — they even have rangers on the trails who randomly chat people up, asking about their destination and preparations.

A Story is Worth a Thousand Words

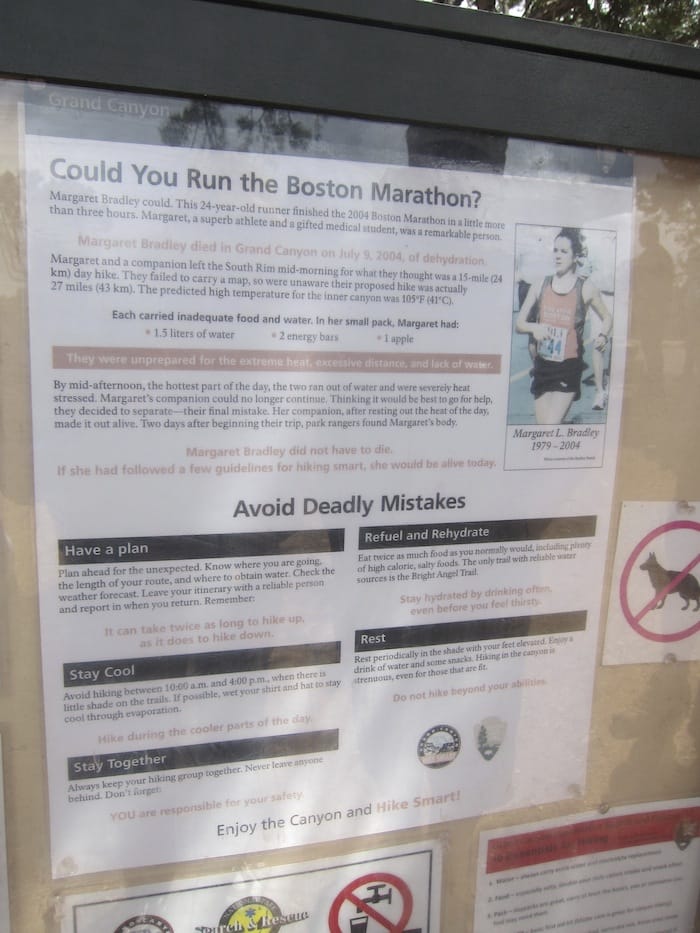

But none of that beats a story about an actual individual. I was at the South Rim on vacation a couple of weeks ago and we came across this flyer posted on a kiosk at one of the major trailheads:

It’s the story of Margaret Bradley, a 24-year-old athlete who ran the Boston Marathon in just over three hours. Yet she died in the Grand Canyon of dehydration. You can read the sad story of her death there on the flyer.

We had a hard time getting a picture of the sign as there were people gathered around reading it. Which is exactly the point.

Why The Story Works

The story is well told:

- It’s got a headline that pulls you in: “Can You Run the Boston Marathon?”

- It includes personal details about Margaret that help you relate to her.

- There’s a photo of her, which is key. Now she looks like someone we know — a sister, a daughter, a friend.

- The photo is captioned with the years of her birth and death, and the tragically small gap between gets your attention.

- It touches on the challenges she and her companion faced and the mistakes they made.

- It reconstructs the pivotal moment that sealed her fate.

- And it ends with the poignant line, “Margaret Bradley did not have to die.”

Ideally, if you’re a hiker about to set out for the trail, you’ll think twice about whether you’re prepared.

The Story Behind the Story

Later I checked online and found the full story, which is even more sad and strange than depicted on the sign. She might have lived if not for some odd communication failures. But I salute the Park Service for focusing on the details that mattered to the audience they’re trying to reach and discarding those that would diminish the story’s power to affect people’s behavior.

For instance, Margaret and her friend had apparently set out to run, not just hike, the trail that day. If that detail had been included, it would be easier for people to dismiss the warning — “Oh, I’m just hiking, not running.” But that may not have had any impact on the outcome, given their under-preparation.

Why Stories Rule

Margaret’s story works because it’s full of drama and conflict. It’s got a relatable character at its heart. It puts a face on an otherwise abstract issue. It packs emotion. And it connects us to each other — we’ve all been lost, tired, alone or injured ourselves or feared for the safety and health of our loved ones.

The fact that this came from an agency of government — not exactly known for innovation and creativity — is probably surprising to some. But governments (that is, people working in government) deal with issues of human interest every day, and probably have lots of worthwhile stories that can help others.

We’re subjected to scores of warnings in our daily lives, from food and medicine labels to highway signs to instructions for electronics and appliances. If only more of those warnings included powerful stories.