With the approach Thursday of the second anniversary of my father’s death, I’ve felt a sort of vague, tired lethargy that I recall from last year, too.

Coincidentally or not, I just finished reading The Things They Carried, the beautiful and heartbreaking book of the Vietnam War, and that’s stirred up a lot of thoughts and emotions.

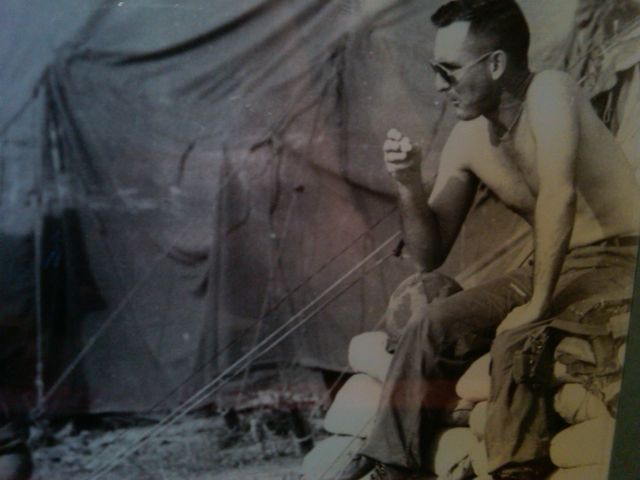

Dad never really talked about his year in Vietnam, and we never really asked about it. But I’ve always been curious about what he and millions of young people like him went through in combat.

That may be why I have a shelf full of books devoted to the subject.

This book in particular really touched me. It speaks to the terrible burden we put on these kids. The things we ask of them, and the many things we’d rather not know about their experience, lest it give us pause the next time we send our children to war in our name.

The Things They Carried

The book’s titular phrase is both literal and figurative:

Every third or fourth man carried a claymore antipersonnel mine, 3.5 pounds with its firing device. They all carried fragmentation grenades, 14 ounces each. They all carried at least one M-18 colored smoke grenade, 24 ounces. Some carried CS or tear gas grenades. Some carried white phosphorous grenades. They carried all they could bear and then some, including a silent awe for the terrible power of the things they carried …

They carried all the emotional baggage of men who might die. Grief, terror, love, longing — these were intangibles, but the intangibles had their own mass and specific gravity, they had tangible weight. They carried shameful memories.

In a poignant NPR segment with the author, Vietnam vet Tim O’Brien, veterans were invited to call in and answer the questions, “What did you carry? What do you still carry?”

They talked about the tangible and the intangible things — the mundane and the heartbreaking.

What My Father Carried

My dad carried a lot of things home from the war. Some I know, some I suspect, some I’ll never have an answer to.

First and foremost, he carried the ticking time bomb of agent orange exposure. It’s been definitively linked by the government to the prostate cancer he recovered from and suspected in the early onset of Alzheimer’s Disease that eventually took his life almost 50 years after he returned from the war.

Which is a reminder that even those who come back home in one piece don’t come out unscathed.

He carried a lot more inside that I’ll never know. He wasn’t what they call a “grunt” — he was a young officer running an artillery unit as part of the revered 101st Airborne. But I believe he did struggle, especially early on, with the things he saw and did there.

What He Brought Home

As for the tangible things, here are three things I remember.

He brought back (or sent home) these elaborately costumed Japanese dolls that my sisters loved. (Maybe he was on leave in Japan?) He brought me back a doll, too, which may seem odd, but I was four and the doll was a boy. I still have it:

I remember when I’d get angry with him I’d throw the doll in a wastebasket, only to guiltily fish it out later.

I remember when I’d get angry with him I’d throw the doll in a wastebasket, only to guiltily fish it out later.

He also brought back a mortar fragment, which somehow I got custody of and kept. Every time I find it in an old box and pick it up I’m surprised by its weight.

It’s sharp as a razor around the edges, and I imagine it whistling through the air, white hot and lethal, at thousands of feet per second.

The Sandal in the Toolchest

The third thing he carried home we no longer have. It was a black sandal, made from a tire tread, and supposedly belonging to a Viet Cong soldier.

How he came back with that sandal I can’t be sure of. I heard stories when I was a kid, but stories are just that — they’re not always the truth. I can’t even remember if what I heard was from him or from my older siblings. They told me lots of stories, most of which I believed.

(Once they had me convinced that Dad got into an argument with a man who let his dog relieve itself on our lawn and actually punched the man in the face. It was only after I shared the news with a disbelieving friend that I learned Dad just yelled at the man.)

What I was told about the sandal was that it came off the foot of a dead Viet Cong soldier, who was laying among a pile of other dead Viet Cong soldiers.

Did that happen? Did dad see that? Did he take the sandal off the man’s foot?

Or was it given to him? Or merely found on some trail or even purchased or traded like a souvenir? Who knows?

For years that sandal resided in a wood cabinet in our unfinished basement, stored alongside hammers and screwdrivers and sandpaper. Sometimes when a neighborhood kid was over I’d open the cabinet and give him a peak and tell him the story as I knew it.

Somewhere along the line the sandal was lost or likely discarded — as far as I know, at least.

And that gets to one of the central themes of The Things They Carried. More than a collection of stories about the war, it’s a meditation on storytelling itself — what’s true and what’s not. Whether the truth is even possible to determine, and whether that even matters.

I don’t need to know the “true” story of that sandal to know that my father, a young man not even thirty years old, saw and did things in Vietnam that nobody should have to see and do.

What Did You Do in the War, Daddy?

I loved playing “war” when I was kid, even more than Cowboys and Indians. You’d stage battles with your friends. You’d compose elaborate, dramatic, acrobatic death scenes.

So it was with this view of the fun and adventure of war that I once excitedly asked my dad, “Did you kill anyone over there?”

He snapped, “I don’t know! I certainly hope not!”

I felt terrible at the time and never brought it up again.

Looking back, I don’t know whether he really didn’t know. I use that phrase all the time when I’m not ready or interested in answering a particular question.

What I do know is that it doesn’t matter. Because it’s clear enough what happened over there based on the fragments of things he did share. The jagged piece of mortar shrapnel, the black sandal, and the story about the night one of the men in his unit woke up screaming in agony. It turns out scorpions had gotten into his sleeping bag.

Dad said that in Vietnam when you took off your boots at night you had to be sure to cover them with your socks to keep the scorpions from crawling in.

That was just a small fact of daily life over there.

After the War

By the time he retired after 20 years of service, Dad was disillusioned with the army, to say the least. He was pretty independent-minded, so I think the bureaucracy and inflexible authority of the military were stifling for him.

But in later years, I think he came to a sense of peace — with the service and with himself. He proudly flew the American flag off his back deck and he expressed his desire to be buried at Arlington, which apparently meant a lot to him. I’m so glad he was able to get that wish.

When I was working on his obituary, I was sorting through his medals and citations, trying to figure out what they signified. A veteran who was there helped me interpret it all.

Some of the commendations, he said, you get just for stepping onto the tarmac in Saigon. Others, like the Legion of Merit … well, these guys don’t get overly animated, but it was very clear he was impressed with the award.

Dad earned it twice.

So whatever happened over there, I imagine he served honorably and did his best (as he tried to do in every area of his life) to cope with a situation that few of us could imagine.

A situation that none of us should have to go through. Which is why I’m constantly dismayed by the cries for war with every new crisis that erupts overseas.

And it’s why the stories of our veterans are more important than ever. We need to listen to them, and ask questions. And, most of all, question everything we’re told by those who would rush us into another conflict.